Inverse element

In abstract algebra, the idea of an inverse element generalises the concept of a negation, in relation to addition, and a reciprocal, in relation to multiplication. The intuition is of an element that can 'undo' the effect of combination with another given element. While the precise definition of an inverse element varies depending on the algebraic structure involved, these definitions coincide in a group.

Contents |

Formal definitions

In an unital magma

Let  be a set with a binary operation

be a set with a binary operation  (i.e., a magma). If

(i.e., a magma). If  is an identity element of

is an identity element of  (i.e., S is an unital magma) and

(i.e., S is an unital magma) and  , then

, then  is called a left inverse of

is called a left inverse of  and

and  is called a right inverse of

is called a right inverse of  . If an element

. If an element  is both a left inverse and a right inverse of

is both a left inverse and a right inverse of  , then

, then  is called a two-sided inverse, or simply an inverse, of

is called a two-sided inverse, or simply an inverse, of  . An element with a two-sided inverse in

. An element with a two-sided inverse in  is called invertible in

is called invertible in  . An element with an inverse element only on one side is left invertible, resp. right invertible. If all elements in S are invertible, S is called a loop.

. An element with an inverse element only on one side is left invertible, resp. right invertible. If all elements in S are invertible, S is called a loop.

Just like  can have several left identities or several right identities, it is possible for an element to have several left inverses or several right inverses (but note that their definition above uses a two-sided identity

can have several left identities or several right identities, it is possible for an element to have several left inverses or several right inverses (but note that their definition above uses a two-sided identity  ). It can even have several left inverses and several right inverses.

). It can even have several left inverses and several right inverses.

If the operation  is associative then if an element has both a left inverse and a right inverse, they are equal. In other words, in a monoid every element has at most one inverse (as defined in this section). In a monoid, the set of (left and right) invertible elements is a group, called the group of units of

is associative then if an element has both a left inverse and a right inverse, they are equal. In other words, in a monoid every element has at most one inverse (as defined in this section). In a monoid, the set of (left and right) invertible elements is a group, called the group of units of  , and denoted by

, and denoted by  or H1.

or H1.

A left-invertible element is left-cancellative, and analogously for right and two-sided.

In a semigroup

The definition in the previous section generalizes the notion of inverse in group relative to the notion of identity. It's also possible, albeit less obvious, to generalize the notion of an inverse by dropping the identity element but keeping associativity, i.e. in a semigroup.

In a semigroup  an element x is called (von Neumann) regular if there exists some element z in S such that xzx = x; z is sometimes called a pseudoinverse. An element y is called (simply) an inverse of x if xyx = x and y = yxy. Every regular element has at least one inverse: if x = xzx then it is easy to verify that y = zxz is an inverse of x as defined in this section. Another easy to prove fact: if y is an inverse of x then e = xy and f = yx are idempotents, that is ee = e and ff = f. Thus, every pair of (mutually) inverse elements gives rise to two idempotents, and ex = xf = x, ye = fy = y, and e acts as a left identity on x, while f acts a right identity, and the left/right roles are reversed for y. This simple observation can be generalized using Green's relations: every idempotent e in an arbitrary semigroup is a left identity for Re and right identity for Le.[1] An intuitive description of this is fact is that every pair of mutually inverse elements produces a local left identity, and respectively, a local right identity.

an element x is called (von Neumann) regular if there exists some element z in S such that xzx = x; z is sometimes called a pseudoinverse. An element y is called (simply) an inverse of x if xyx = x and y = yxy. Every regular element has at least one inverse: if x = xzx then it is easy to verify that y = zxz is an inverse of x as defined in this section. Another easy to prove fact: if y is an inverse of x then e = xy and f = yx are idempotents, that is ee = e and ff = f. Thus, every pair of (mutually) inverse elements gives rise to two idempotents, and ex = xf = x, ye = fy = y, and e acts as a left identity on x, while f acts a right identity, and the left/right roles are reversed for y. This simple observation can be generalized using Green's relations: every idempotent e in an arbitrary semigroup is a left identity for Re and right identity for Le.[1] An intuitive description of this is fact is that every pair of mutually inverse elements produces a local left identity, and respectively, a local right identity.

In a monoid, the notion of inverse as defined in the previous section is strictly narrower than the definition given in this section. Only elements in H1 have an inverse from the unital magma perspective, whereas for any idempotent e, the elements of He have an inverse as defined in this section. Under this more general definition, inverses need not be unique (or exist) in an arbitrary semigroup or monoid. If all elements are regular, then the semigroup (or monoid) is called regular, and every element has at least one inverse. If every element has exactly one inverse as defined in this section, then the semigroup is called an inverse semigroup. Finally, an inverse semigroup with only one idempotent is a group. An inverse semigroup may have an absorbing element 0 because 000=0, whereas a group may not.

Outside semigroup theory, a unique inverse as defined in this section is sometimes called a quasi-inverse. This is generally justified because in most applications (e.g. all examples in this article) associativity holds, which makes this notion a generalization of the left/right inverse relative to an identity.

U-semigroups

A natural generalization of the inverse semigroup is to define an (arbitrary) unary operation ° such that (a°)°=a for all a in S; this endows S with a type <2,1> algebra. A semigroup endowed with such an operation is called a U-semigroup. Although it may seem that a° will be the inverse of a, this is not necessarily the case. In order to obtain interesting notion(s), the unary operation must somehow interact with the semigroup operation. Two classes of U-semigroups have been studied:

- I-semigroups, in which the interaction axiom is aa°a = a

- *-semigroups, in which the interaction axiom is (ab)° = b°a°. Such an operation is called an involution, and typically denoted by a *.

Clearly a group is both an I-semigroup and a *-semigroup. Inverse semigroups are exactly those semigroups that are both I-semigroups and *-semigroups. A class of semigroups important in semigroup theory are completely regular semigroups; these are I-semigroups in which one additionally has aa° = a°a; in other words every element has commuting pseudoinverse a°. There are few concrete examples of such semigroups however; most are completely simple semigroups. In contrast, a class of *-semigroups, the *-regular semigroups, yield one of best known examples of a (unique) pseudoinverse, the Moore–Penrose inverse. In this case however the involution a* is not the pseudoinverse. Rather, the pseudoinverse of x is the unique element y such that xyx = x, yxy = y, (xy)* = xy, (yx)* = yx. Since *-regular semigroups generalize inverse semigroups, the unique element defined this way in a *-regular semigroup is called the generalized inverse or Penrose-Moore inverse. In a *-regular semigroup S one can identify a special subset of idempotents F(S) called a P-system; every element a of the semigroup has exactly one inverse a* such that aa* and a*a are in F(S). The P-systems of Yamada are based upon the notion of regular *-semigroup as defined by Nordahl and Scheiblich.

Examples

All examples in this section involve associative operators, thus we shall use the terms left/right inverse for the unital magma-based definition, and quasi-inverse for its more general version.

Real numbers

Every real number  has an additive inverse (i.e. an inverse with respect to addition) given by

has an additive inverse (i.e. an inverse with respect to addition) given by  . Every nonzero real number

. Every nonzero real number  has a multiplicative inverse (i.e. an inverse with respect to multiplication) given by

has a multiplicative inverse (i.e. an inverse with respect to multiplication) given by  (or

(or  ). By contrast, zero has no multiplicative inverse, but it has a unique quasi-inverse, 0 itself.

). By contrast, zero has no multiplicative inverse, but it has a unique quasi-inverse, 0 itself.

Functions and partial functions

A function  is the left (resp. right) inverse of a function

is the left (resp. right) inverse of a function  (for function composition), if and only if

(for function composition), if and only if  (resp.

(resp.  ) is the identity function on the domain (resp. codomain) of

) is the identity function on the domain (resp. codomain) of  . The inverse of a function

. The inverse of a function  is often written

is often written  , but this notation is sometimes ambiguous. Only bijections have two-sided inverses, but any function has a quasi-inverse, i.e. the full transformation monoid is regular. The monoid of partial functions is also regular, whereas the monoid of injective partial transformations is the prototypical inverse semigroup.

, but this notation is sometimes ambiguous. Only bijections have two-sided inverses, but any function has a quasi-inverse, i.e. the full transformation monoid is regular. The monoid of partial functions is also regular, whereas the monoid of injective partial transformations is the prototypical inverse semigroup.

Galois connections

The lower and upper adjoints in a (monotone) Galois connection, L and G are quasi-inverses of each other, i.e. LGL = L and GLG = G and one uniquely determines the other. They are not left or right inverses of each other however.

Matrices

A square matrix  with entries in a field

with entries in a field  is invertible (in the set of all square matrices of the same size, under matrix multiplication) if and only if its determinant is different from zero. If the determinant of

is invertible (in the set of all square matrices of the same size, under matrix multiplication) if and only if its determinant is different from zero. If the determinant of  is zero, it is impossible for it to have a one-sided inverse; therefore a left inverse or right inverse implies the existence of the other one. See invertible matrix for more.

is zero, it is impossible for it to have a one-sided inverse; therefore a left inverse or right inverse implies the existence of the other one. See invertible matrix for more.

More generally, a square matrix over a commutative ring  is invertible if and only if its determinant is invertible in

is invertible if and only if its determinant is invertible in  .

.

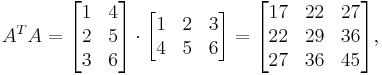

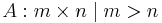

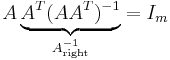

Non-square matrices of full rank have one-sided inverses:[2]

- For

we have a left inverse:

we have a left inverse:

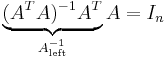

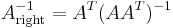

- For

we have a right inverse:

we have a right inverse:

The right inverse can be used to determine the least norm solution of Ax = b.

No rank-deficient matrix has any (even one-sided) inverse. However, the Moore–Penrose pseudoinverse exists for all matrices, and coincides with the left or right (or true) inverse when it exists.

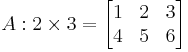

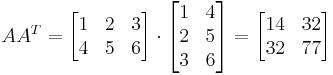

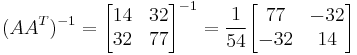

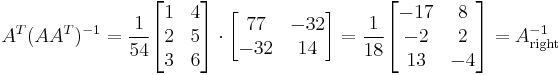

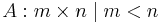

As an example of matrix inverses, consider:

So, as m < n, we have a right inverse.

The left inverse doesn't exist, because

which is a singular matrix, and cannot be inverted.

See also

Notes

- ^ Howie, prop. 2.3.3, p. 51

- ^ MIT Professor Gilbert Strang Linear Algebra Lecture #33 – Left and Right Inverses; Pseudoinverse.

References

- M. Kilp, U. Knauer, A.V. Mikhalev, Monoids, Acts and Categories with Applications to Wreath Products and Graphs, De Gruyter Expositions in Mathematics vol. 29, Walter de Gruyter, 2000, ISBN 3110152487, p. 15 (def in unital magma) and p. 33 (def in semigroup)

- Howie, John M. (1995). Fundamentals of Semigroup Theory. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-851194-9. contains all of the semigroup material herein except *-regular semigroups.

- Drazin, M.P., Regular semigroups with involution, Proc. Symp. on Regular Semigroups (DeKalb, 1979), 29–46

- Miyuki Yamada, P-systems in regular semigroups, Semigroup Forum, 24(1), December 1982, pp. 173–187

- Nordahl, T.E., and H.E. Scheiblich, Regular * Semigroups, Semigroup Forum, 16(1978), 369–377.